By Syed Wajid Ali

Licensing Framework is one of the fundamental building blocks of telecommunications regulations.

Currently, PTA is in the process of reviewing its existing framework in the light of Telecommunication Policy – 2015. An international consultant has been hired for the purpose and he has been mandated to come up with his recommendations on the following aspects of the framework:

- Section 20 of the Telecom Act, and in particular, which over-the-top services should be licensed under a “General Authorization” in which a service provider is deemed to hold a license by virtue of the services that it provides and is then subject to the terms of that General Authorization, which may include national security requirements;

- Whether there should be a separation of spectrum and operations licensing;

- The requirements for licensing of satellite services specified elsewhere in this Policy;

- The requirements for licensing public Wi-Fi metropolitan area networks;

- The requirement for spectrum related licensing for non-public telecommunications use such as amateur radio, maritime and aviation uses;

- In addition to the specific cases listed above, the extent to which telecommunications and content services require licensing;

- Whether distinctions should be maintained between different license types, and if not, the implications of removing such distinctions including the rights and obligations of existing licensees that would need to be transitioned;

- The method of licensing of those organizations that hold a broadcasting license to offer telecommunications services to ensure equivalent treatment of alternative infrastructure providers;

- The licensing of telecommunications licensees for the provision of broadcast media and/or distribution service, including the necessity of doing so given the evolving nature of TV.

Before we have a look at the International Best Practices for telecommunications regulation to answer these questions, there is a basic set of principles that have been adopted at the international level by the World Trade Organization (WTO). Their Reference Paper contains the key regulatory policy principles that member countries must adhere to.

For the purposes of this article, the relevant principles include:

- Prevention of anti-competitive practices in telecommunications

- Interconnection to be ensured under non-discriminatory terms, no less favorable than that provided for its own like services and cost-oriented rates that are transparent, reasonable, having regard to economic feasibility, and sufficiently unbundled so that the supplier need not pay for network components or facilities that it does not require for the service to be provided

- Public availability of the procedures for interconnection negotiations, transparency of interconnection arrangements and dispute settlement

- Public availability of licensing criteria

- All the licensing criteria and the period of time normally required to reach a decision concerning an application for a license and

- The terms and conditions of individual licenses.

- The reasons for the denial of a license will be made known to the applicant upon request.

- The regulatory body is Independent from, and not accountable to, any supplier of basic telecommunications services. The decisions of and the procedures used by regulators shall be impartial with respect to all market participants.

- Any procedures for the allocation and use of scarce resources, including frequencies, numbers, and rights of way, will be carried out in an objective, timely, transparent and non-discriminatory manner. The current state of allocated frequency bands will be made publicly available, but detailed identification of frequencies allocated for specific government uses is not required.

Best Practices on a Global Scale

With this background in mind, now let’s have a look at International Best Practices. The goal is not to imply that there is only one course of action that PTA must follow in developing this framework. Nevertheless, the experiences of other countries and the widespread adoption of the WTO principles are useful to demonstrate what has been shown to work in other countries. By adopting an approach that encompasses widely tested and accepted best practices, the Government of Pakistan will maximize its ability to achieve its goals in a timely fashion.

As addressed below, a liberalized and unified licensing framework are hallmarks of a licensing regime aligned with current international best practices. Key elements of such a framework include technology and service neutrality, as well as rules that afford regulatory certainty while remaining flexible enough to accommodate the dynamic telecommunications market.

- Liberalized licensing framework A liberalized framework allows the telecommunications sector to transition from a monopoly to a thriving, competitive market by facilitating new entry; thereby improving service quality and selection, reducing prices and increasing access to new and innovative services.

- Technology and service neutrality Incorporating technology-neutrality into a licensing framework allows operators to choose which type(s) of technology to deploy and use, while a service-neutral framework enables operators to offer any type of service to end users. Technology and service neutrality involves moving away from service-specific licenses in which an operator must hold a separate license for each type of network and/or service it offers.

- Flexible licensing framework Alongside the introduction of technology and service neutrality, regulators are streamlining their licensing frameworks and allowing for unified licensing which permits operators to offer all services – or at least a broad range of services – under a single license. Unified (or integrated) licensing both simplifies the licensing process to promote new entry and competition, as well as enables existing operators to more easily expand their service offerings by eliminating the need to obtain a new license for each new service added to the network, which significantly delays the roll-out of new and innovative technologies and services.

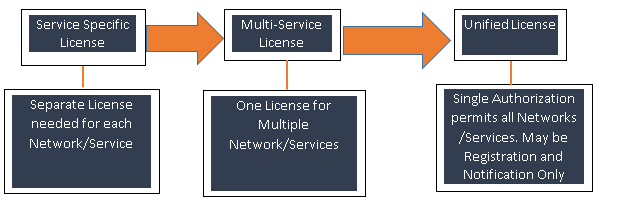

- Multi-service telecommunications licensing approach As shown in Figure 1, a multi-service licensing approach provides an intermediate step between service specific licensing and a fully unified licensing regime or general authorization. Unlike with a service-specific regime, a multi-service licensing framework allows providers to offer multiple services under the umbrella of a single authorization, using any type of communications infrastructure and technology capable of delivering the services in question. As such, multi-service licenses are technology- and service-neutral within the designated set of authorized services. However, a multi-service approach is not as streamlined as the general authorization framework, which provides the greatest ease of entry, is fully technology- and service-neutral and is often subject to simple registration or notification processes. Singapore, Jordan, South Africa, and Malaysia have adopted the approach of Multi-service telecommunications licensing. Mainly they have segregated their licensing regime between facilities-based and services-based licensing, however, Malaysia has four categories namely Network Facilities Provider, Network Service Provider, Application Service Provider, and Content Application Service Provider. On the other hand, Member States of the European Union transitioned from service-specific licensing regimes to a general authorization regime in 2002. Member States were required to amend their laws to facilitate entry and innovation through the least onerous authorization system possible. This was seen to be best achieved by general authorization of all types of electronic communications networks and services without requiring prior permission from the regulator – procedural requirements are registration/notification only.

In transitioning to a more unified licensing regime, existing service-specific licenses should be examined to determine whether, based on current objectives, such services should still be licensed separately or as part of a unified regime, be subject to registration/notification only, or be exempt from licensing.

From Service-Specific to Unified Licenses:

- Separation of spectrum and operations licensing. The more unified the framework, the greater the ease of entry and deployment of new and innovative services. As such, the simplest licensing framework should be adopted, to the extent permitted by law. Unified frameworks still generally require separate authorizations for the use of scarce resources, particular access to spectrum. There should be no pre-determined cap on the number of licensees in order to facilitate market entry. Referred to as “open entry,” any applicant that satisfies the application criteria should be granted a service/operating license. However, the grant of a service/operating license does not guarantee access to scarce resources, such as spectrum, which are generally obtained through a competitive bidding mechanism. This separation of the spectrum and operations licensing and open Entry are required to encourage optimal utilization of spectrum through spectrum sharing and trading with those licensees.

- Licensing application process In addition to a more simplified licensing framework, the processes for granting licenses and authorizations should be published, streamlined and standardized, in line with the WTO Reference Paper

- Standardized process. This includes publishing a standard application with instructions for completing and submitting the application. A standard application means that all applicants for a certain license category use the same application with the same information requirements, unless there is an objective reason for differentiation, in order to ensure parity and transparency.

- Application Requirements. The amount and type of information to be provided by applicants should be proportionate to the type of license sought. For example, proof of financial or technical expertise is generally not warranted for class licenses, whereas a facilities-based individual license would likely require the applicant to demonstrate financial and technical capabilities. Extensive administrative procedures are costly to both applicants and the regulator, requiring more resources and longer timeframes.

- Timeframes. License processes should also promote efficiency by including timeframes for the regulator to make a decision and requirements for the regulator to provide written reasons for refusing to grant a license. The timeframe for evaluating a completed individual license application should be 40 working days and 30 working days for a class license application, with an additional 15-day for public comment period for both. The Instructions set forth the possible reasons for rejection of an application, such as prior noncompliance with the telecommunications laws and regulations, failure to pay previous fees or lack of financial or technical capabilities. Any rejection must be provided to the applicant in writing with the reasons for rejection clearly stated.

- License term. License durations vary around the world and are often different for different types of service. In Malaysia, for example, a spectrum assignment is valid up to 20 years. Likewise, in many European countries, initial 3G licenses were valid for 20 years, although Sweden limited its licenses to 15 years. For commercial mobile licenses, the initial licenses are generally valid for a minimum of 15 years. The regulator may determine, as part of the consultation on the licensing process, what the actual duration should be in specific cases. Many countries limit the duration of the initial license term to 25 years.

- Mobile Offloading or WiFi Offloading. The proliferation of mobile broadband devices such as smartphones, tablets, wireless dongles, and demand for new data-intensive applications along with the unlimited data plans from the operators have fueled the increase in mobile data usage. According to a recent report by Cisco, Overall mobile data traffic is expected to grow to 49 exabytes per month by 2021, a sevenfold increase over 2016. Mobile data traffic will grow at a CAGR of 47 percent from 2016 to 2021. (Source: Cisco)

Increase in mobile data usage puts a lot of pressure on the capacity of the existing networks. The availability of additional radio spectrum resources and deployment of higher performance technologies, such as LTE, may enhance existing network capacity. This capacity development, while significant, falls well short of what is needed to meet future mobile broadband demands. This will lead to network congestion and deterioration of network quality, which consequently leads to poor quality of experience for customers. Moreover, adding capacity to the wireless network is a significant investment and thus operators are looking at alternative approaches to deliver more capacity in a cost-effective manner.

Further, Spectrum is a scarce resource. The wireless segment is witnessing unprecedented growth. As the demand for wireless connections continues to grow, the service providers need to efficiently utilize available spectrum and data offloading techniques may play a substantial role here.

To address this issue, service providers should embrace “Mobile Data Offloading”, which allows operators to alleviate network congestion quickly as it is flexible in its deployment options and is applicable to both LTE and 3G wireless networks. Traffic Offload refers to the ability to move mobile data traffic from one network to another in a way that is transparent to the subscriber. It can be done either by an end-user (mobile subscriber) or an operator.

As radio spectrum is limited, network congestion and deterioration of network quality will become inevitable for operators due to the unprecedented growth of data traffic in future. Even deployments of new technologies, although having better spectral efficiency may not be able to handle network data capacity commensurate to future mobile broadband demands. In such circumstances offloading of data, traffic will be a viable solution as it provides not only relief from an increased growth rate of data traffic but will also help operators reduce costs.

In view of the above, it is recommended to plan the deployment of WiFi/Femto/Pico mesh at a commercial building, Universities, railway stations, airports, and public places & transport.

Convergence of Telecom and Media Broadcasting/Distribution Services

As per the Telecom Policy – 2015, while developing the new licensing regime the following will be taken into account:

“The licensing of telecommunications licensees for the provision of broadcast media and/or distribution service, including the necessity of doing so given the evolving nature of TV.”

Majority of the Telecom Companies are Foreign Owned & Section 25 of PEMRA Ordinance, 2002 doesn’t allow a company having the majority of shares owned or controlled by foreign nationals to obtain TV License.

In our view, Section 25 does not differentiate between a broadcasting license and a distribution license. We understand the legislators’ intent in restricting the foreign majority shareholding is related to broadcasting only and that is why PEMRA is given the power to exempt an applicant from this restriction. Section 32 of PEMRA Ordinance, in conformity with the principles of equality and equity as enshrined in the Constitution, allows PEMRA to grant exemptions by giving reasons in writing. Such exemptions to the provisions of the Ordinance may be granted in public interest.

PEMRA may, therefore, grant general exemption of foreign shareholding for distribution Services to the telecommunication operators by invoking Section 32.

- Over The Top (OTT) Services. Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) and OTTs increasingly compete across a number of market domains and product areas (voice, text, content, cloud). Each respective industry appears to be governed by, or take different account of, regulations, taxation, and labor & privacy laws. These asymmetries are providing a competitive advantage to OTTs also yielding significant economic benefit. Among these areas of asymmetries, there are at least 3 areas that can be directly advocated by MNOs to get a more level field with OTTs: Customer Data protection; Consumer protection; Law enforcement. Beside this OTTs have also now started end to end encryption, OTTS, therefore, should either be asked to adopt standard encryption otherwise telecommunication Operators may also be given relief for the following reasons before granting OTTs General Authorization by just asking them to provide Legal Interception in lieu.

- QoS of Telecom Operators: Encryption affects the quality of services required by the Regulator, e.g. because it would prevent efficient traffic management.

- Network security and integrity: MNOs must guarantee the integrity of their networks and must also notify any security breach or loss of integrity. OTT encryption can affect security and integrity of networks to the extent that they restrict the MNOs’ ability to track malware and other intrusions.

- Cooperation with law enforcers (copyright infringements): MNOs have no obligation to monitor the data they transmit or store. As MNOs might be required by court orders or national laws to block illegal websites, OTT encryption can prevent such blocking.

- Data retention obligations: MNOs are required to keep certain data including IP address, user ID, etc. to allow identification of the source, destination, type and time of the communication, equipment used and location, etc. OTT encryption prevents retention of data.

ALSO READ

PTA to Record User Data from All Public Wi-Fi Hotspots

The trend towards liberalized and technology-neutral licensing frameworks began decades ago, with many countries around the world having now adopted some degree of unified licensing, such as all EU Member States, Canada, Jordan, Kenya, Korea (Rep.), Nigeria, Thailand, Uganda and the United States, in addition to Singapore, South Africa, and Malaysia. While the precise mechanism that is implemented varies from country to country, there is a general trend in developing licensing frameworks that follow most, if not all, of the elements described below:

- The more unified the framework, the greater the ease of entry and deployment of new and innovative services. As such, the simplest licensing framework should be adopted, to the extent permitted by law.

- Unified frameworks have a separate authorizations for the use of scarce resources, particular access to spectrum.

- These are technology and service neutral, which permits operators to offer all services enabling existing operators to more easily expand their service offerings by eliminating the need to obtain a new license for each new service added to the network, which significantly delays the roll-out of new and innovative technologies and services.

- There should be no pre-determined cap on the number of licensees in order to facilitate market entry. Referred to as “open entry,” any applicant that satisfies the application criteria should be granted a service/operating license. However, the grant of a service/operating license does not guarantee access to scarce resources, such as spectrum, which are generally obtained through a competitive bidding mechanism.

- In transitioning to a more unified licensing regime, existing service-specific licenses should be examined to determine whether, based on current objectives, such services should still be licensed separately or as part of a unified regime, be subject to registration/notification only, or be exempt from licensing.

- OTTs to be brought under licensing regimes in view of the ongoing terrorist activities worldwide. Moreover, instead of end to end encryption, they should be asked to go for standard encryption and also provide the Legal Interception to the Law Enforcing Agencies.

- Mobile Offloading or WiFi Offloading may be encouraged in the wake of unprecedented data growth vs scarcity of spectrum.

- Convergence of Telecom and Media Broadcasting/Distribution Services

The author served as the Former Head of Regulatory and Interconnect at Jazz.

Thak gya bhai scol kr kr k.?

Foreign ownership must be limited. Whereas India has the likes of Reliance Jio and Tata Telecom, Pakistan doesn’t have one locally owned and operated player. Even in the Middle East and even USA broadcasting and other licensing is not given out to foreign controlled operators. This should be the case in Pakistan also. Otherwise Pakistanis will only continue to beggars and our profits will go to build networks in Egypt and Bangladesh like the case with Mobilink/Jazz/Orascom.

Fully agree that restriction should be on broadcasting license but not on distribution license. Business activities should not be stopped for the fear of outflow of money. For that other measures can be taken.