By Momin Imran Sheikh

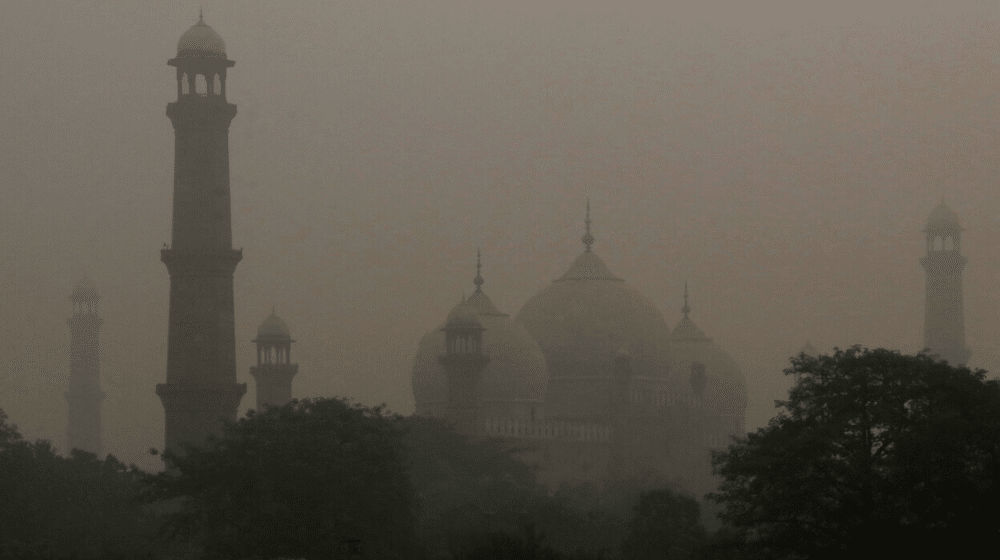

If you experience symptoms of sore throat, headaches, itchy eyes, and breathlessness, it is because Lahore is running out of air to breathe. The city now offers a toxic concoction of vehicle exhausts, burnt diesel, and smoke from garbage as an alternative to air. Consequently, vulnerable people are at risk of contracting diseases, and asthma and chronic heart diseases are also being triggered by the smog. You know a city has failed when its doctors advise you to stay indoors and avoid exercising for health reasons.

As the city recovers from almost two years of pandemic-induced lockdowns, it is being gripped by a public health crisis larger than the last one. Although this crisis has been highlighted for a few years, it has taken an extreme turn this time because of the smog.

A thick grey haze now covers all of Lahore. Most of the city’s vehicle fumes and emissions from diesel generators, lorries, and industries stay suspended in the atmosphere as lack of wind flow and cool temperatures prevent their dispersion.

Besides the callousness of the authorities, the Punjab Minister for Environment Protection refuses to accept the existence of smog despite Lahore being officially recognized as the world’s worst city in terms of air pollution. Lahore’s smog crisis is decades in the making, and one cannot expect a lasting solution unless the city’s authorities review its development policies that have pushed the city to this crisis.

Lahore’s emissions remain constant year long, and one of the main reasons behind the smog becoming a crisis in autumn is the wind patterns over the region that decelerate this time of the year, causing the pollutant particles to accumulate in the atmosphere.

The citizens get to see a visible representation of the pollutants that are emitted on an average day. Many steps, such as banning the burning of crops, and the shutting down of brick kilns during the smog season to control it, have had little effect because the major contributor of smog remains the emissions from within the city. The major contributors are transportation, private vehicles, and lorries with their diesel engines, and the intracity industries.

Lahore’s transportation was completely revamped in the last two decades to rely solely on private vehicles, although most of the population was not able to afford cars. The incomplete public transportation system has been heavily criticized by the incumbent government for being expensive as it would rather invest taxpayers’ money in more roads and bigger highways to make newer areas attractive for real estate developers — a particular model of development that also contributes the most to smog.

Local public transportation commuters are subjected to vile situations. For example, there are garbage dumps at the entrances of the Orange Line Metro’s stations, and metro buses regularly display notices reminding users of the subsidy being provided for their commute. Commuters are also discouraged from using public transportation, with a notable government representative going as far as saying that instead of using public transportation, each commuter should be given a private car from the money.

Moreover, Lahore’s road tilt is so heavy that even the sidewalks and safety features for pedestrians have been removed to make the roads almost completely vehicle reliant. The city roads, where one would expect heavy pedestrian activity, have been turned into signal-free highways that almost divide the communities they pass through, and render pedestrians so unsafe that walking on the road is no longer an option. One must rely on their car or motorbike to cross the road.

Interestingly, vehicle emissions have never been considered in Lahore’s urban planning models that are mostly focused on an aesthetically pleasing town plan and pay little attention to the functionality of the plan. The outsourcing of the development and growth of the city to housing scheme developers has reduced Lahore’s administration to a road constructing authority that turns pedestrian-friendly roads into highways and takes it deeper into suburbs on the city’s periphery. This allows housing developers to develop more suburbs, which, in turn, only increases Lahore’s reliance on cars in the absence of reasonable public transportation.

If any junction in the city has more than a hundred people stuck at a traffic light (a relatively low number for a city of over 10 million people), it gets turned into an overhead bridge or an underpass with increased pedestrian restrictions. This only attracts more vehicles via the concept of induced demand when roads are expanded and pedestrians are restricted. It only makes them choose cars to travel over it, which increases the traffic that the road widening was supposed to reduce.

Despite Lahore catering so much to cars, car owners comprise only a fraction of its population. According to registered vehicle statistics, the number of cars is only 22 percent of the city’s entire vehicular traffic. Considering the city’s population, the number of cars is less than 10 percent of the city’s population. Given how most car owners possess multiple vehicles, the percentage of people owning vehicles in Lahore is even lower.

However, the number of motorbikes is significantly higher — almost thrice the number of motorcars. This number has also increased significantly — almost 2.5 times between 2010–2017 (although the number may be even higher today). Bikers are the most affected by the lack of adequate public transportation and are most likely to be the first beneficiaries if public transportation is improved but the city focuses almost entirely on catering to the car population than actual commuters.

The result of this heavy disparity between cars and motorbikes, and discouraging pedestrians or any form of non-motorized transportation (like cycling) is that the city has turned into one giant road with lots of vehicles which causes breathable air to turn into vehicle exhaust. Studies indicate that roughly 50 percent of Lahore’s emissions are from the transport sector alone. Every year, for months at a time, the city reminds its residents of the effects of its poor choices. Ironically, the authorities are completely ignorant of how reducing the number of vehicles on the roads can help prevent the production of smog. Nonetheless, there is a glimmer of hope as most of the new public transport buses are electric, which will help control fuel emissions.

The second-largest contributor to Lahore’s smog is the industrial areas that were once at the periphery of the city but are now located close to the populated areas because of uncontrolled expansion. The industries in these areas have recently had all their regulations for smoke emissions revoked. The industries refuse to repair or replace their substandard equipment that releases smoke so thick that a cloud of smoke engulfs the entire surrounding even on a relatively clear day.

Even worse is the policy of pushing diesel generators into every household to counter Pakistan’s power issues a decade ago. Every residential, commercial, and public building, including bus stations and many urban and suburban houses, now has diesel generators that provide backup power during load shedding. To make things worse, Pakistan uses diesel of the lowest standards than anywhere else in the world, making diesel generators another major emitter across the city. This is another policy decision that the city’s planners failed to consider the environmental impact on, and environmental assessment for any public work remains a box-ticking exercise at most.

Lahore’s problem of smog is not unique. Many cities in the world have grappled with the problem and solved it, such as London’s infamous smog of 1952 and Beijing in the 2010s. The solution that will have the most significant impact in improving Lahore’s air quality is also the one that will upset its car-obsessed elite (a mere 10 percent of the population according to most estimates) the most. Regardless, Lahore must reverse its car-centric design.

Lahore should also make pedestrian-only and bicycle zones all over the city, besides urgently arresting the widening and ‘highway-ization’ of city roads which only compounds the traffic problem as it attracts more cars on the roads through induced demand. Public transportation must also become the major focus of the city’s planning authorities, for numerous reasons, and not just in terms of controlling emissions.

A Vehicle Inspection System, which has long been intended but is dead, must also be revived to weed out vehicles that are unfit for travel in terms of emissions and road safety. This criterion must also be more stringently followed for vehicles with diesel engines.

Industry emissions must be monitored, and they must be mandated to treat their smoke emissions. The phasing out of diesel engines and generators must also be agreed upon with the industries falling within or close to the city centers. Also, diesel power backup generators must be removed from all over the city as the power issues have mostly subsided and solar backup has become a reasonably cheap alternative.

Lahore is no longer a mere suburb, it is now considered an international metropolis, and must abandon its car-centric urban design unfit for cities of this scale. It would also do well to arrest its rapid suburban growth, unless a reasonable mode of transportation (other than cars) is provided in the suburbs. As most successful cities of Lahore’s scale already have them, Lahore will also have to start demolishing its signal-free highways to become a more people-friendly city.

Lastly, urban forests alone cannot counter Lahore’s excessive smog, and the city’s emissions must be actively reduced before anything other measures can be taken into consideration.

Momin Imran Sheikh is an environmental activist, working as an Urban Development Specialist in Lahore