Which language has not been the oppressor’s tongue?

Which language

truly meant to murder someone?

And how does it happen

that after the torture,

after the soul has been cropped

with the long scythe swooping out

of the conqueror’s face –

the unborn grandchildren

grow to love that strange language

– A Different History, Sujata Bhatt

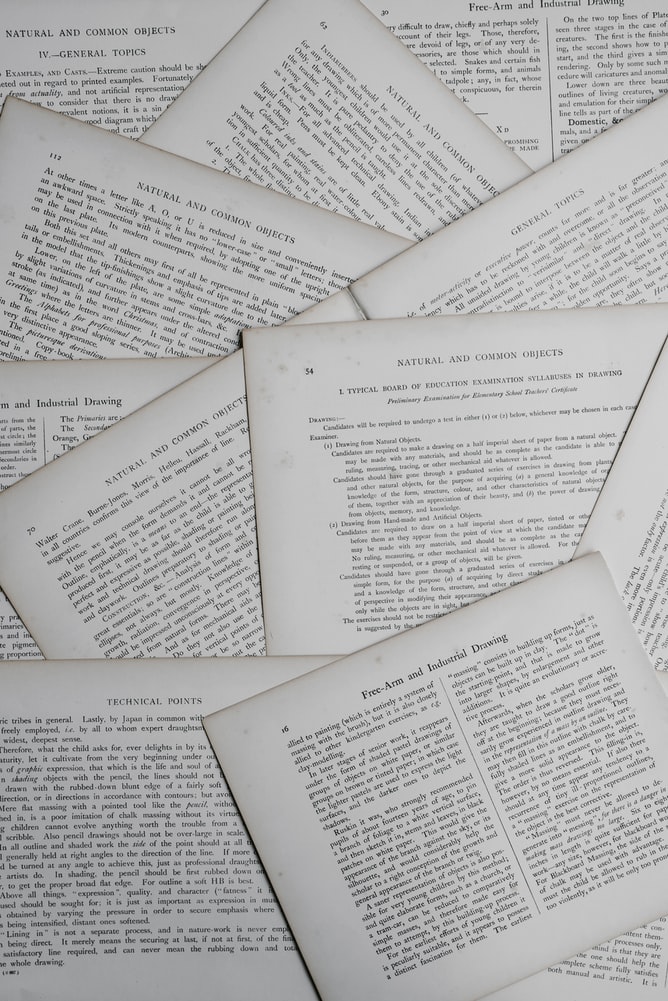

The debate around the dominance of the English language is ongoing in many Pakistani circles, especially as of late as many have raised their voice to claim back the importance of Urdu as their own heritage and identity.

The conversation around language and identity is based in a much larger shift in global politics right now that is recognizing the damaging effects of ‘othering’. But have we ever stopped to think that this ‘othering’ begins at home?

The internet, social media, and rise of global media conglomerates have made access to media and information a lot smaller. But promoting Western media content to the rest of the world has led to the dominance of a very ‘white’ narrative – one that seeks to change the way we see and understand even our own identities. And most of the time, we fail to understand how deeply entrenched this mindset has become.

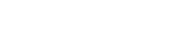

Language in particular is an interesting concept to look at. Pakistan’s own history with language, particularly the selection of Urdu as a national language (and English as another official language alongside) has been the center of heated debate and opinions. The history of languages as part of both official and unofficial state narratives play a key role in the formation of identities.

The question is – what happens when one language starts to dominate the media we consume? By media, I don’t mean just Hollywood. This is true for the influx of English-language books as well.

The dominance of English in Pakistan has not only meant a sidelining of Urdu but a distinctive ‘othering’ of the language that is meant to be solely ours.

It’s bad enough that English literature and publications abroad feel the need to italicize foreign words and languages. In doing so, they promote the idea that anything other than English is exotic and different, and therefore those who rely on those languages become equally different.

But when did we start ‘othering’ ourselves? In my exploration of Pakistani literature and even media publications, I’ve come across the italicization of Urdu far too many times to count.

Is it because we want to appear ‘westernized,’ which we often associate with progress and modernity? Or an unconscious feeling of adapting whatever trend western culture throws our way?

Is the fear real?

In my conversation with author Moni Mohsin last month, we came across this very debate. Why is it that we feel an excessive need to constantly explain and elaborate on ourselves to make our culture and language accessible to a white audience?

In the interview, Mohsin said she struggled to convince her publisher to retain certain words and phrases she felt were key to her story as worked on The Diary Of A Social Butterfly. A charpai after all, is not a bed – and maintaining what may seem like small differences is vital to preserving key parts of our own identity.

Case in point, celebrated children’s author Enid Blyton never felt the need to explain what jodhpurs were to her young international readers. Why does the onus fall on brown writers like Mohsin to accommodate others when in doing so, she risks alienating her own.

ALSO READ

Young Author Highlights ‘Pashtoon Heroes’ in His First Book [Video]

Our culture is not made to be broken down into bite-sized easy to swallow chunks that can be lapped up by white audiences whenever they feel like being ‘woke’. It is a representation of who we are. We shouldn’t; owe no apologies to anyone for not being understandable in the way they would like.

There are countless books that have great storylines but immediately put me off because of their over-explanation of Pakistani culture which I find very hard to swallow. Because if we do start pandering to Western ideals of how our culture should be accessible to others, who will tell our future generations to hold on to this part of their identity that is theirs.

What may seem like a blip in the editing business is in fact so much more. We pick and choose words to italicize based on the needs of an audience that’s not our own, and that apologetic overdoing nature becomes a part of who we are.

We apologize for existing. For being too much. For being not enough. For being too brown. For saying salan instead of curry.

Where do we stop? How long until our own children forget that Urdu was ever more than the italicized words others choose to identify us with. Because when we italicize our own language, we make it foreign to ourselves. And somewhere down the line of our children and their children, we risk making them ourselves foreign to them.

What do you think?

I love to speak for my mother tongue. I am an English Teacher at an English medium school and my friend is an Urdu teacher. We always debate about this issue as students find English more convenient these days and are leaving urdu behind. We should campaign for this at national level. I hope all us, like minded people come together and make Urdu language and culture our pride.