If you’ve been keeping an eye on Pakistan’s agriculture scene or dared to dip your toes into the world of agribusiness, you’re probably no stranger to this blame game. Farmers struggling with abysmal crop prices and consumers grappling with soaring inflation, all pointing fingers at the middleman, (of course after the sitting government).

The theory often presented to the public is that the middleman is all evil in the supply chain and eliminating him will fix everything. But let’s not miss the bigger picture here – it’s an outcome, not the root cause.

You must have caught those news segments with anchors prowling grocery markets, grilling ordinary shoppers about price discrepancies. But have you ever witnessed a media maven venturing into the heart of grain markets or mandis, where the real action unfolds, where farmers, middlemen, and retailers strike wholesale deals?

We leave the reasons behind this curious omission to your imagination. But who is the shadowy figure said to be pulling the strings in the agricultural supply chain, leaving state regulators powerless and driving the market for their own gains and does he even deserve all this criticism he gets?

Who is the Middleman?

A middleman more commonly known as Arthi is someone sitting between the farmers and the retailers or end consumers in the agri-supply chain. He provides farmers with seeds, fertilizers and chemicals as interest-based loans and also buys their produce at cash payment and near their village without a hustle providing him with a complete hegemony over the supply chain of essential commodities.

For starters, let’s be clear that Middleman is integral to any market economy as most agriculture production happens far from urban centers and you can’t possibly have farmers running down to cities and retailers to sell their produce. You need someone to assume the risk which is not within the scope of farmers and consumers.

There are primarily two types of middlemen, merchants and agents. Merchants include wholesalers and retailers who buy the product, take ownership of the inventory, incur the costs of storing and distributing it and make money by selling it at a margin. Agents are simply brokers specialized in negotiation and charge fees for facilitating transactions.

Agriculture middlemen also provide other essential services as well like market information, lending, logistics, quality control and above all, access to wider markets that farmers may not be able to reach on their own.

But he also gets the blame and often rightly so for farmers not getting the right value, exploiting his position as a lender to force farmers into selling crops to only him at lower prices, charging more fees as well for the whole thing and hoarding the commodities to drive up the prices and the criticism is not isolated to Pakistan but exist across all developing economies and it’s not limited to price discrepancies.

There are a whole lot of generic and adulterated seeds and agrochemicals that grow and feed upon this exploitation. Since most of the loans taken by farmers are centered around these products, middlemen get to choose which company’s seeds and chemicals the farmer should buy ultimately lowering yields. On top of that, this kind of market manipulation scares local or international organizations from investing in R&D and developing the market, bogging down the agricultural productivity of the whole country for the coming decades.

“There are multiple problems with the current system of middlemen. For starters, there are too many of them. You have some at the village level and some at the grain market and in total there are five to six middlemen between farmer & consumers and since there is no transparency in this supply chain, the farmer gets half the value it deserves.” stated Usman Mahar, Progressive farmer and co-founder Roshan Kisaan Cooperative while talking to ProPakistani.

He added that the market is supposed to finance farmers but it offers lower prices to borrowers than those who don’t owe money and while middlemen are essential for the system, it should be fair to both farmer and the consumer.

While it’s true that the middleman is often blamed for the whole mess alone by other stakeholders not willing to take responsibility for their own inefficiency, when a single economic class is given nearly absolute advantage as happened with middleman Pakistan, you’re bound to have some people looking to exploit farmers and consumers for their financial gains.

Throwing Out Middleman is Not a Fix

The conversation about eliminating middlemen is mostly centered around agricultural markets but the problem is as mentioned earlier, there will be a middleman in a supply chain in one way or the other, whether we have some guy sitting in a mandi or some company claiming to connect farm to retail or more special, farm-to-fork model to reform agriculture supply chain.

Middleman has been made into look as that boogeyman that is the root of all evil in part for diverting attention from successive governments abandoning the agriculture sector for years and ignoring the fact that the middleman’s relationship with the farmer exists because nobody else is there to provide the same service or value.

While we have banks and a few agritech startups working on agri-financing and supply chains, the problem is a lot bigger and deeper to solve through an app or even a credit-scoring model. A farmer cannot possibly throw his relationship with a middleman in the trash for a startup that may not be around next year which is not out of the question and even most of these companies had to procure from middlemen, instead from farmers.

“Since the farmer lacks financial resources for timely storage and labor, even his good crop is sold for lower prices,” added Mahar. He concluded that our current agriculture model is not sustainable enough and brings too much uncertainty to assure the farmer if he gets financing, he will be able to pay it as well.

One way of shortening the supply chain and eliminating unnecessary middlemen is to finance the SME clusters near villages and zones of production which will create rural employment and will automatically bring value to farmers and consumers alike.

As far as agritech is concerned, these startups had to acknowledge how critical the ‘boogyman’s role’ was in farming communities. it is going to take some time for any digital solution to arrive and build and provide a similar level of security that the middleman provides but even then eliminating the middleman is not a fix and is not possible.

That’s because the problem is not having a middleman or even the fact that there are exploitative individuals within their ranks but the real problem is him being the sole source of access to capital for farmers.

He is not just a farmer’s lender, he is his brother, father, a friend in all good and bad times. A farmer can knock on their door for a loan to educate their children, celebrate a wedding, or cope with a family tragedy. Who else can provide such a lifeline for farmers? Banks? Not so sure about that.

Credit is the Elephant in the Room

State Bank of Pakistan launched a reformed Agriculture Loan Scheme after the 1972 Banking Reforms when the Agriculture Credit Advisory Committee (ACAC) was set up and first-ever assessments on credit requirements were made based on acreage and cost of fertilizers, seeds, and pesticides. Over the decades, this scheme has been revamped and improved multiple times but it has largely failed to improve farmers’ standard of living or raise the level of agriculture productivity at scale.

Financial Institutions distributed Rs. 1.77 trillion during FY23 and while it experienced impressive growth of 25 percent compared to FY22, it still missed its target which as you can see above, has been happening for years, though the banking industry came awfully close to it. The growth was primarily fueled by the Kisaan Package announced by the previous government for flood-affected regions, agriculture machinery and related proposes.

Moreover, Pakistan Agriculture Credit has actually been declining over the last decade in dollar terms amid massive devaluation in recent years and that matters because agriculture inputs namely high-quality hybrid seeds, machinery, agrochemicals and even some key fertilizers like DAP are majorly imported.

Pakistan Agri Credit share in Value Added Agriculture GDP has nearly halved between 2013 and 2021 from 4.24 percent to 2.57 respectively.

Prices of these inputs have risen several times while the agriculture credit has shown negative growth in dollar terms in similar times.

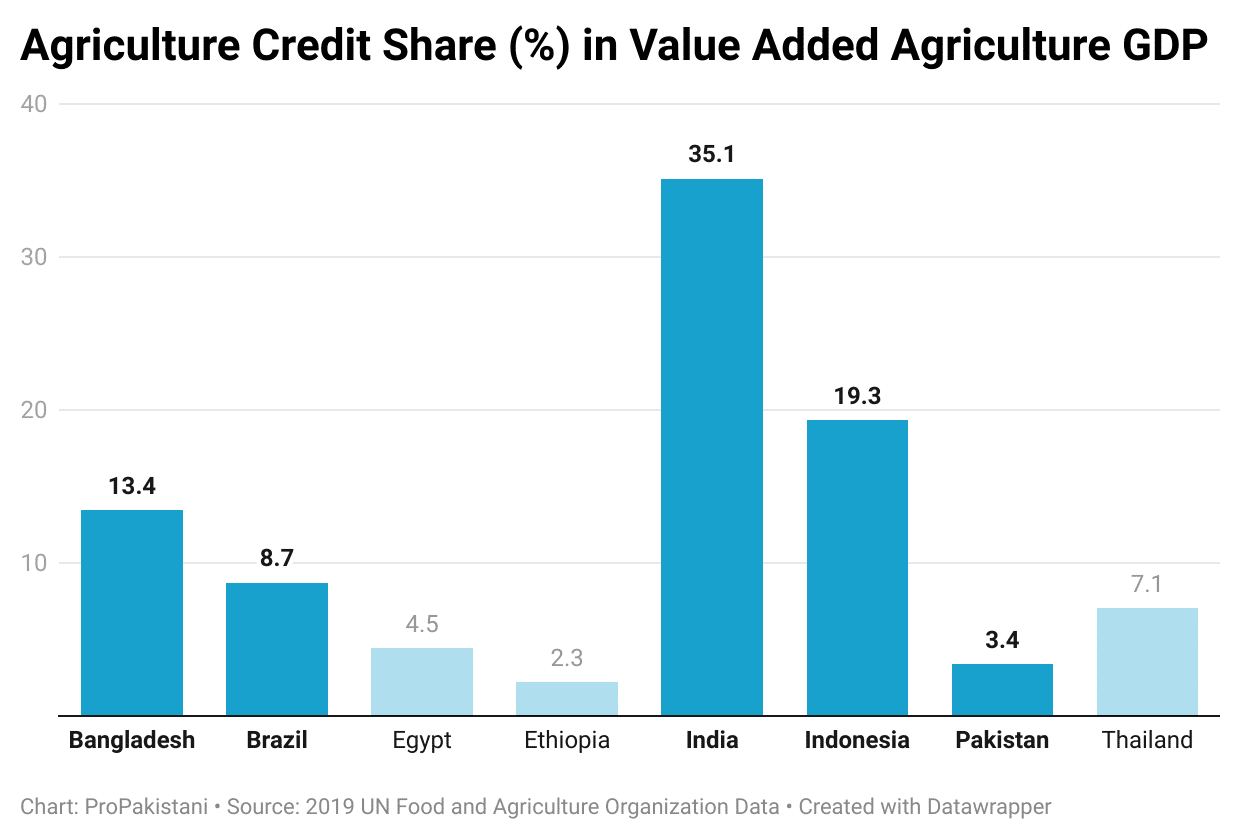

Pakistan’s Agriculture Credit Share to Value Added Agriculture GDP was a mere 3.4 percent as of 2019 which is nowhere close to regional competitors like India (35.1%), Bangladesh (13.4%), Indonesia (19.3 percent), Brazil (8.70 percent) or Thailand (7.1 percent). It’s evident from the above chart that growth in agriculture is simply not possible without easing the agriculture credit. In the end, everything comes down to priorities.

Unfortunately in Pakistan, getting a loan as a farmer is not remotely as simple for a farmer as it is for an industrialist with an established record but we have discussed these matters in the past as well and since rarely anything changes around here we will be brief.

There are cumbersome processes and documentations, a demand for collateral most farmers lack, credit allocation based on the recipient’s political clout rather than his productivity and efficiency and the banking sector’s inherent reluctance to hedge bet against unpredictable weather patterns & other calamities by investing in farming when they have government as their biggest lender.

Conventional banking institutions have provided the vacuum themselves by not giving real value to the farmers or at least being actual competitors to non-institutional credit which has resulted in the middleman having a lot more leverage than what we might usually have in a more competitive environment.

We all hail the free market economy and peddle against government intervention in agriculture markets but even without the government intervention, it’s not a free market. It’s a monopoly at best and exploitation at worst since the farmer has nowhere else to go and the other side knows it.

Rebuilding the Agriculture supply chain is a whole other ball game but agri-financing at the government level is a part of it and fixing it alone can do a lot more good than blazing empty guns at someone who is not going anywhere for the foreseeable future.