Does anyone know what a digitally enabled farm would be like?

Well, that’s what this writer was wondering at a recent roundtable organized by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) with the Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI) on a potential digital growth strategy for Pakistan.

ADB has historically invested in Pakistan around infrastructure and energy, but as they are looking to invest and raise the digital profile of the country, they have organized a roundtable with people from the private sector and academia to frame a policy for future transactions around this area.

Coming from an agricultural background, this writer would love digitization to take over this critical sector that accounts for a quarter of the GDP, so today, our goal is to separate fiction from reality and some buzzwords from real solutions. What it means to Pakistan and what it doesn’t and how we can get there.

Will we have crops sending text messages about their health, tractors cruising fields using GPS, or cows rocking fitness trackers, or our digitization would be somewhat different from all of that?

Digitizing the agriculture sector simply means infusing tech-enabled data gathering, decision-making, and operations across the supply chain from seeds to fork. All to raise productivity and transparency, reduce losses, and make better choices for an uncertain future riddled with a worsening climate change crisis.

The sector finally received some spotlight in major policy circles after devastating floods in 2022, so it is hoped that our bureaucracy is as serious for a change this time, otherwise, these choices will be made for us by some thousands of billion tons of CO2 floating right above us in the atmosphere.

I had personally tailored my discussion around four or five primary areas, most of which are universal for all the sectors. Telecom, Education, Banking and Payments, Taxation, and Agriculture itself because these are the ‘analog rails’ over which you would think to digitize anything but that’s just an opinion.

But first, let’s have some shock therapy of what we are dealing with at the moment.

What’s the State of Affairs?

Let’s begin with agriculture. While studying it, they teach you the seven principles from seed & site selection to post-harvest management, and it wouldn’t surprise you a bit to know that in Pakistan, that whole chain is dinged up in every way imaginable.

Land fragmentation, soil degradation, low R&D base, unapproved varieties, mounting irrigation losses, reliance on shrinking manual labor, overuse of fertilizers and chemicals, and the worst kind of agri marketing system that promises farmers anything but value. All of it translates to the lowest productivity of key crops in the region and post-harvest wastage that keeps the sector in the stone age where it was considered enough to grow for yourself and your family.

The Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC) launched the Land Information Management System (LIMS) to rationalize data gathering and availability across farmers, industry, and academia. It’s part of the Green Pakistan Initiative that is propelling corporate farming and capital into the country, so agriculture will be happening at a scale to justify the use of center-pivot irrigation, drones, and other advanced machinery.

But most of it’s going into lands not cultivated before and, amid top-level secrecy around the initiative, it’s still unclear if and how these initiatives will affect average farmers. Let’s move to telecom, where the digitization was supposed to begin!

Telecom

Pakistan ranked 79th out of 100 countries on the Economist’s Inclusive Internet Index in 2022, last out of 22 countries in Asia. India and Bangladesh ranked 50th and 64th respectively, while countries like Egypt (57th), Lebanon(74th), Sri Lanka (59th), and even Myanmar (69th) beat us to it which has been in a civil war for years.

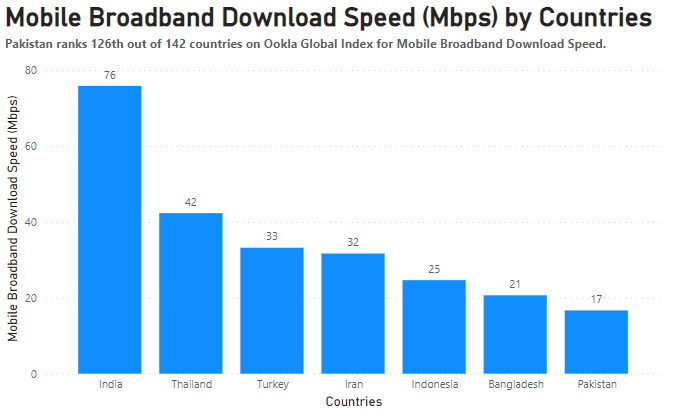

The country has also the lowest broadband speeds in the region and ranks 126th on the Ookla Global Index, with download speeds lower than even countries like Iran and Somalia, both of which have been under sanctions for decades.

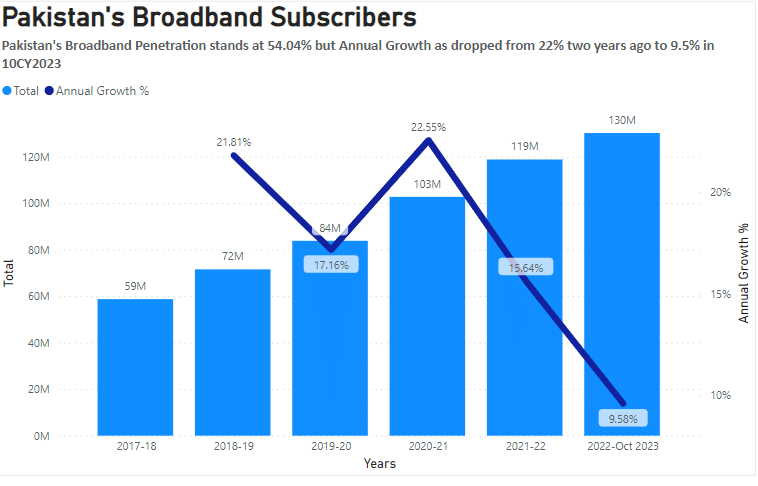

Annual growth in Pakistan’s Telecom sector slumped to single digits (9.58 percent) till October 2023 with Average Revenue Per User (APRU) dropping to the lowest ($0.80) in the world as per media reports, with two telcos alone reporting Rs. 30 billion in losses in 2022.

The crisis is driven by skyrocketing finance costs in light of interest rate hikes, dollarization of cost structure and massive devaluation, rising energy, electricity, and other operational costs, and repressive taxes which have worsened the financial health of the sector.

The crisis has heavily impacted infrastructure development, with nearly all cellular marketing operators (CMOs) calling for improving the existing 4G spectrum rather than pursuing 5G connectivity.

Telecom is important because some great solutions on which agritech startups are working, can’t possibly be implemented without basic connectivity while others require far more broadband penetration, adoption, and affordability to come up with meaningful results and these companies can’t expand further into digitization while incurring heavy losses.

Recommendations here can’t be more obvious. The government recently approved a new Telecom infrastructure sharing framework, which should in theory reduce operational costs. The government also has to begin by delinking the telecom cost structure from the dollar and the relief measures should be expanded in the upcoming government.

Education

Coming to education, Pakistan has reportedly 62 percent literacy rate against India (76 percent), Bangladesh (75 percent), Iran (89 percent), Turkey (97 percent), and Indonesia (96 percent).

Education has simply never been considered fancy enough to spend time, investment, and political capital.

Unless and until primary and secondary education is reformed, building new universities, starting new skill training programs and even industry-led efforts will have limited success.

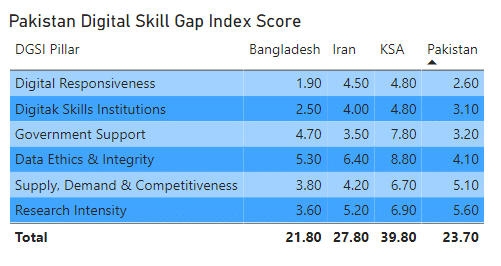

Pakistan ranked 94th out of 134 countries on the John Wiley Digital Skills Gap Index (GDSI) scoring 3.9, with India, Iran, and Bangladesh standing at 56th, 81st, and 106th respectively.

As for students, the goal in my opinion should not be to only build IT training institutes, as it’s not 90s any more.

Anybody willing with a good device and internet connectivity can learn anything online these days, but the goal should be to instill enough critical thinking and self-awareness, so youth can decide where they want to end up in their lives. The biggest drag is the lot lacking all motivation to learn and unaware of what they should learn.

As for consumers or rather farmers, the story gets more complicated.

In a recent NIC event in Faisalabad, I asked the founders of two agritech startups what their biggest challenge and their answer was ‘technical illiteracy in farmers’ I was a little surprised because something like that should have been factored in already in their business models. If farmers had that much technical literacy, what makes anybody think we wouldn’t already have agritech solutions sprawling across the country?

We also need to figure out what some mean by the technical illiteracy of farmers. Smartphone and social media usage are well tuned in villages, so why farmers won’t jump into an agritech app left and right when you take it to them?

Banking & Payments – Looking for A Silver Bullet!

“The biggest enabler I have seen in executing digital transformation in China is payments. As long as you don’t bring users to tap to pay or QR codes, the phone adoption will stay limited to social media,” stated Tabbish Mahmood, Lead of Digital Transformation at Syngenta talking to ProPakistani.

He added that digital transformation is a huge challenge, but it won’t begin with farmers but input, output dealers, and companies. Once these people who are literate enough realize the value of digital payments and app-based advisory services.

He also recalled how Syngenta is placing POS machines to record the secondary sales and give some resistance they are encountering, he also mentioned the need for regulatory incentives to attract the arhti rather than providing open subsidies on commodities.

The government recently launched Raast Person to Merchant services and all eyes are now on how banks and major fintech players leverage it and how SBP navigates the challenges that will be coming the way.

You know, you go ask farmers what’s their biggest problem, they will only tell you two things: they are not getting the right price for their inputs and outputs. They won’t cite the need for an agritech app or high-tech sensor in the field.

And that’s the answer to the earlier question of why most farmers do not jump in readily on agritech solutions being offered. Our farmer is unable to see anything beyond black marketing of key inputs and market manipulation of unseen proportions.

The road of B2C digitization in agriculture goes through B2B. Some startups realized it earlier in their journey, for some, it was too late and some are still wandering around.

What It Will Achieve?

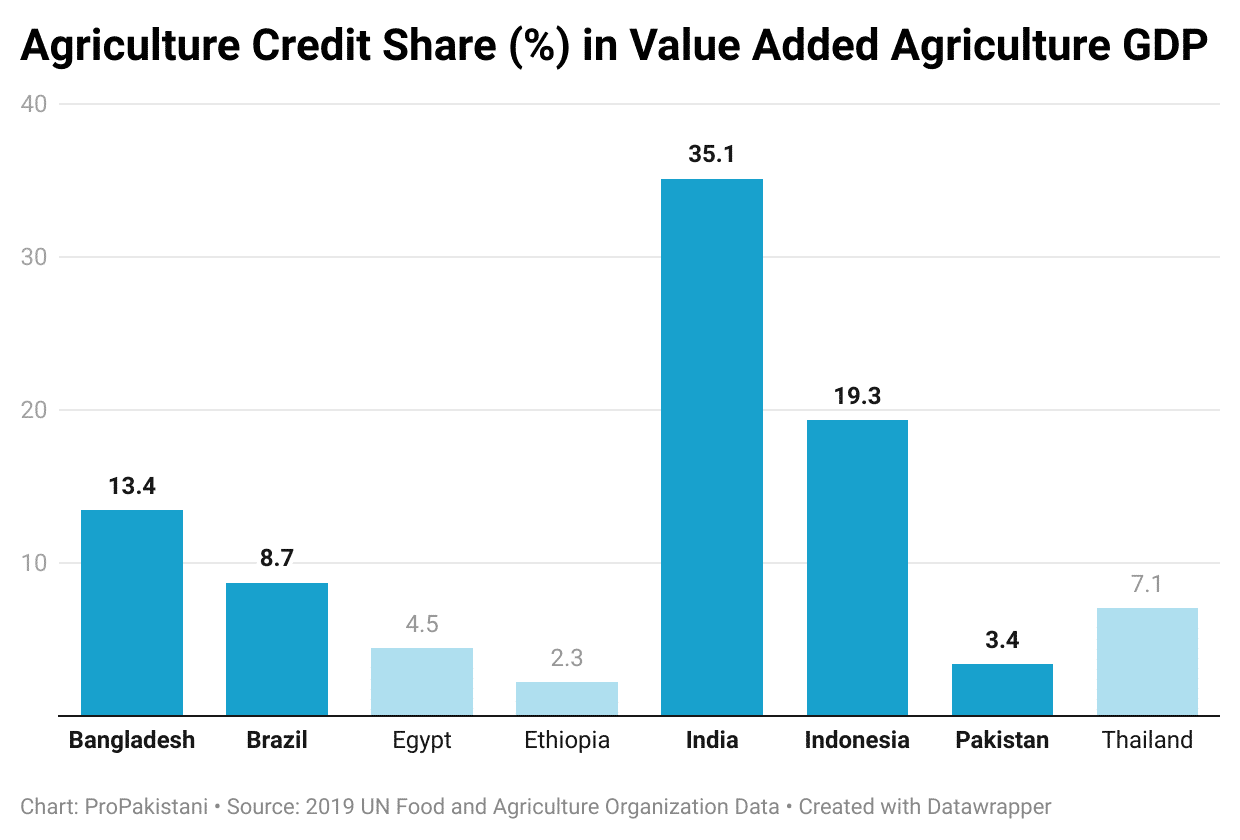

For this writer, digitizing a few hundred gain markets and dealerships will achieve four things. First, we will have a credit history for farmers to move capital into the uncertain landscape of agriculture. We have the lowest agriculture credit to value-added agriculture GDP ratio in the country, and it’s about time that rather than blaming middlemen for exploitative lending, we start doing something about it.

Secondly, we will have enough trusted market intelligence data for agile policymaking around trade and agriculture, which is the need of the hour for the climate change crisis we are living in.

Nobody in the private sector trusts the government numbers on wheat production and the poultry feed industry fears the government aggressively exploring corn exports since we might export more than what we have in excess (which happened with sugar and wheat in the past) and then there is a 40 percent import duty.

India restricted rice exports in August, but they are selling at higher prices in government-to-government deals. How? Since they know how much they have and how much they can export without affecting their domestic prices.

Third, the resultant transparency in the system will build farmers’ trust in both ends of the supply chain, and we may end up requiring fewer subsidies if a farmer is okay with a bad year, believing it happened for the right reasons rather than exploitation.

Farmers understand the profit and loss, but not exploitation, and digitization is the only road to that transparency.

Lastly, this along with fixing the income tax loophole for agriculture (for big landlords) and preventing post-harvest losses in the ecosystem can potentially raise enough money to replace subsidies and phase them out gradually. That money can then be invested back in digitizing the farmers.

Mahmood added that one more challenge for the government is execution amid the lack of budgets, expertise, and the level of project management needed, so the better play will be to provide a framework for the private sector.

“There are no short-term wins here. It’s about moving the whole ecosystem together and if we start digital transformation today, maybe in 20 years or more, we will have some realization of the vision” added Mahmood.

Is it a long and bumpy road? Yes. Is it possible? Of course, yes. The government has demonstrated over time with the recent example of the forex and gold market that when there is willingness, it finds its way.

I can train and move farmers to digitalization ASAP by splitting areas into zones and zones to volunteers with another specialised app. Please give me contact to some of these startups and mehmood sb. I also have knowledge how to increase productivity and studies to utilise our wasted Govt lands. I’ll make 3 arms of teams to utilise wasted lands.