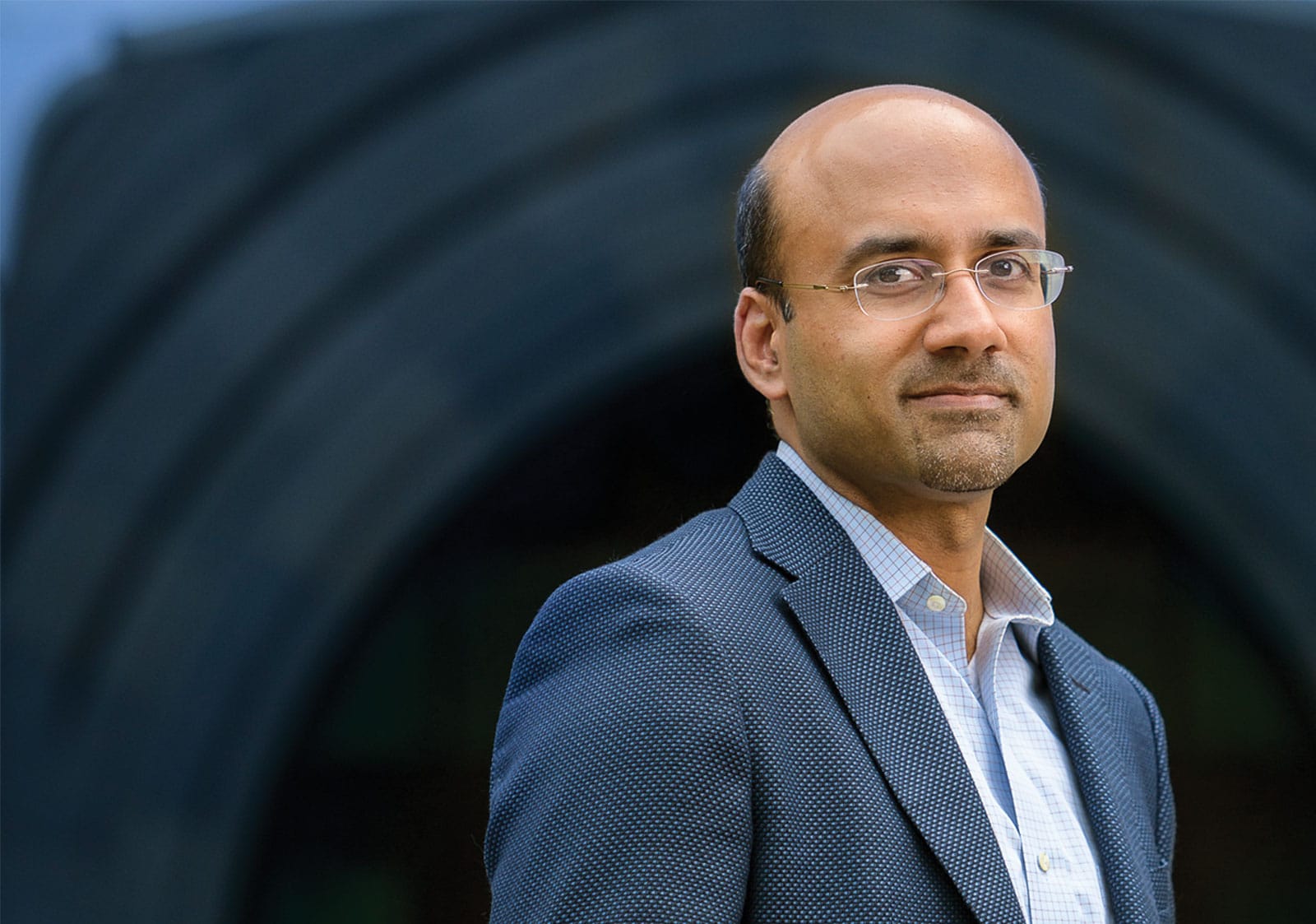

Pakistani-American economist and former member of Pakistan’s Economic Advisory Council (EAC), Atif Mian, has said that Pakistan’s growth process is unbalanced as high growth is fundamentally unsustainable, resulting in a vicious cycle where an uptick in growth is followed by a currency crisis.

The economist took to Twitter to point out systematic flaws in Pakistan’s economy that have led to the current account approaching 5 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP).

Pakistan's current account swung positive when Covid contracted GDP in 2020

But as GDP started recovering in 2021, it has again gone deeply negative – approaching 5% of GDP now

What does this tell us? 🧵

— Atif Mian (@AtifRMian) January 30, 2022

Atif pointed out that Pakistan’s current account swung positive when the GDP contracted in 2020 due to COVID-19. However, as the economy started recovering in 2021, it has severely declined.

He attributed this trend to growth being captured by an unproductive few. The economist said that this disincentives investment in productive capacity making the country less competitive in global exports.

Secondly, he continued, rents earned in unproductive sectors (like real estate capital gains) are used to import goods and services.

Atif pointed out that there is tension between these two forces as the country cannot afford to purchase from the rest of the world if it hasn’t expanded its productive capacity first.

This results in a vicious cycle where an uptick in growth is followed by a currency crisis. He added that this cycle has continued for the last forty years.

Pakistan has poor institutions and therefore a lot of rent seeking activity. Real estate capital gains are just one manifestation, the underlying problem is weak institutions.

Let’s consider the genesis of the macroeconomic crises that we have faced since the year 2000.

Two things come to attention during this period. First, many of these crises were triggered by energy price shocks. Since we import most of our energy, we are vulnerable to sharp spikes in international energy prices. The worst crisis was in 2008 when the unprecedented rise in oil prices wiped out our foreign exchange reserves, inflation spiralled out of control, forcing the SBP to agressively raise interest rates. That brought the GDP growth spurt to an end, and we never really recovered from it.

The second observation is about fiscal discipline and economic mismanagement. This is in part also related to the SBP autonomy being talked about a lot recently.

When the govt fails to collect taxes, it can get the State Bank of Pakistan to print money to cover it’s budget deficit. This tendency is particularly notable among the incumbent governments as they approach the election year.

The result is inflation that exerts pressure on value of our currency. During Dar Sahib’s tenure, currency was not allowed to depreciate resulting in depletion of foreign exchange reserves, and an unprecedented fall in exports to 20 billion dollars from 25 billion dollars.

This episode has been repeated recently with wavering fiscal discipline in the run up to the next elections having coincided with international commodity price rises due to covid-19 related supply disruptions. We are back to IMF.

So the point I am making is that the observed boom bust cycles may be related to electoral cycles, and therefore are political economic in nature.

What is the way forward? Improve institutions. State Bank autonomy is a small step in that direction. But better institutions should also prevent governments from being fiscally irresponsible. They should ensure that more competent persons should be entrusted with economic management. Mr Atif Mian’s resignation is itself a case in point.

However, deeper issues are also involved in economic mismanagement. First, is the generalist nature of civil service managers who regularly make economic decisions. This is not to deny the contribution of civil services cadre in the immediate post independence era and early phase of development. More specialized knowledge is needed today, so civil service reforms that ensure mobility in and out of the services at all levels should get priority.

Second, there are inadequate checks on, or lets say insufficient democratic oversight of elected politicians who make long term economic decisions.

Poorly negotiated CPEC energy deals saddled the economy with expensive energy that hit our comparative advantage. Moreover, the then govt wanted the projects to complete before the elections. It opted for projects based on imported fossil fuels instead of renewables such as hydel or solar energy. This led to increased exposure to international energy price shocks. As I mentioned above, this is one of the key factors that has contributed to boom bust cycles.

Institutional weakness is systemic. Our academia has been unable to link up with our industry to produce genuine comparative advantage dispite significant investments in higher education. We missed the boat on IT revolution, in contrast to our neighbor India. Now we are struggling to adopt artificial intelligence.

We have allowed agriculture to deteriorate. The worst decline is in our cotton, with recent production levels having fallen below what we had achieved in the ’80s. We could not find a solution to the cotton leaf curl virus problem.

Good institution — I am not using the word in the sense of organizations — would have led to formulation of appropriate policies to address these problems.

Nothing epitomizes the institutional decay more than our failure to collect taxes, protect property rights and enforce contracts. Powerful commercial and political interests collude to bring about this outcome. The rents and the black money may be parked in real estate. But if we start fixing the real estate sector without fixing the underlying problem — poor institutions — we would only be applying a band aid to the problem.

A good comprehensive overview on the underlying problems. Thank you.