Cotton, one of the most critical cash crops that support 8 percent of the country’s GDP through the textile sector and nearly 60 percent of the exports, has been struggling to scale production for nearly a decade now.

So much has been written and said about its demise that we often lose track of the challenges that come with not having a viable seed that actually holds the promise of the entire crop.

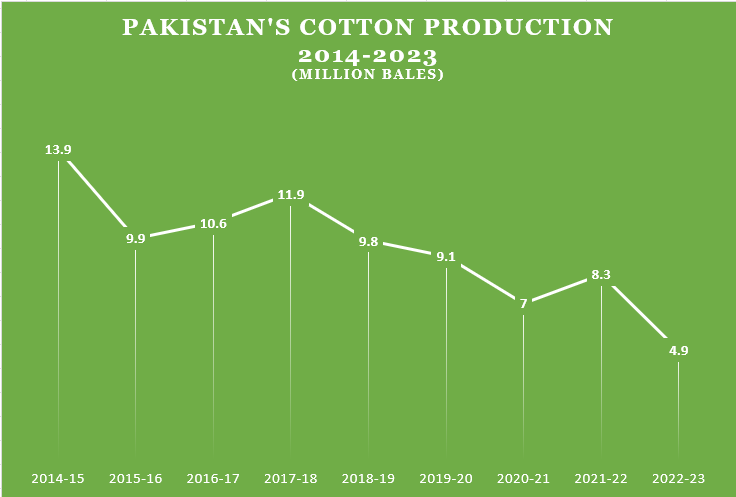

Fortunately, this year’s early reports indicate a bumper crop but that’s because of the relatively mild summer we get to witness during the early stages of the crop and not because we finally fixed the issues that caused a near 65 percent drop in production from 2014 to 2022. So it’s primal to not forget and more so, revisit the history that brought us here in the first place and the bottlenecks which are least discussed in the backdrop of subsidies and price relief.

Story of Pakistan’s Cotton

Let’s brush up on some agriculture basics first. There are primarily three types of seeds most common, open-pollinated varieties (OPVs) involve natural pollination through wind and other mediums, hybrids involve controlled cross-pollination of two distinct parent plants and genetically modified cultivars (GMOs) are developed by the insertion of foreign genetic material into the seed to increase yield or resistance.

So the primary reason we lack high-yield cotton hybrids is that cotton’s manual cross-pollination is highly time-consuming and even then gives a mere 15 percent yield advantage over OPVs. Considering hybrids are always far more expensive and farmers have to buy them every year rather than using the ones stored during the previous year, it’s not much lucrative for seed conglomerates to develop or farmers to adopt.

Monsanto first introduced GMO-based Bollgard or largely known as Bt Cotton (after the common bacterium, B. thuringiensis ) in 1996 with resistance against bollworms in the United States. The foremost problem was that it was originally developed for temperate regions like the Americas and not regions like Pakistan where the average temperature in summer crosses 40 degrees so needed local variants but for that, you need IP rights and here came the elephant in the room.

Bt Cotton first came to Pakistan informally in 2002 and by 2007, nearly 60 percent of the cotton area was under Bt varieties but interestingly, there was no approval yet that could ensure proper utilization of this technology. Between 2002-2010, there were continuous negotiations between Monsanto (now Bayer), the Government of Pakistan and domestic agri-research institutions over developing and marketing the Bt-Cotton or similar varieties in Pakistan.

Multiple entities including the National Institute for Biotechnology and Genetics Engineering (NIBGE), Cotton Research Institute, Multan, Center of Applied Molecular Biology (CAMB), and even a private entity called Neelum Seeds had developed their own versions of Bt Cotton with similar MON 531 sequence for which Monsanto threatened legal action if the seeds were marketed. The litigation could, in theory, disrupt Pakistan’s exports to Europe and North America where Monsanto had strong Intellectual Property Rights protections.

Monsanto itself was unwilling to enter the Pakistani market strategically because it was mostly unregulated with no robust IPR protection. It presented two business models to GoP in 2007 and 2008 both of which involved the government paying Monsanto a fee based on the technology spread which meant, an independent survey would determine the share of Monsanto’s seed technology in the total cultivation every year and the company would be paid accordingly.

A 2021 study by Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) put the figures for annual payment at more than $120 million in 2008 for 80-90 percent seed penetration and for a perspective, that was more than the total budget of the Punjab Agriculture Department during that year so obviously it did not pan out successfully.

On the other hand, the government refused biosafety approvals for all locally developed Bt-cotton varieties believing it would be an official endorsement of IPR infringement. So FMC (American Crop Protection Conglomerate) backed out after signing an agreement with CAMB to develop Bt-cotton and Neelum Seeds’ offer of a JV was shunned by Monsanto and its variety Bt 121 was banned from cultivation across the country.

The LUMS study also revealed that these actions further pushed Bt-cotton into the unregulated sector only to find out that Monsanto’s claim that its international patent of Bollgard extended to Pakistan as well was questionable at the least. The study states that not only Monsanto lacked the patent, it could not patent it as well per Patent Ordinance 2000 since it was already disclosed in public.

“Regardless of the means of how germplasm was brought into the country, the government should have clamped down immediately. We required the Bt technology to better improve our local cultivars and not the varieties themselves but the lack of government inaction and no public-private partnership resulted in people only using it for financial gains”, stated Kassim Motiwalla, founder of Fortune Farms Cooperative and Agribusiness executive with 15 years of experience working in Bayer and Engro talking to ProPakistani.

He said that these foreign varieties were developed in line with their specific weather and pests as Australia witnessed Aphid pest attacks while Pakistan has Jassid and the United States does not have a big whitefly challenge, unlike Pakistan and India. Both of these factors demanded the further development of cotton varieties which unfortunately could not be realized.

The lack of any ownership, formal regulation and domestic development prevented the Bt-cotton from resulting in expected production increases and periodic modifications as resistance against pests and challenges from climate change grew with time. The informal market only strengthened with time as locally developed Bt varieties slipped into the farmers’ hands with the absence of any suitable alternatives.

Where Pakistan Stands Now?

Interestingly, cotton and wheat are the only two crops for which private trade and the marketing of imported seeds are banned through the 1976 Plant Quarantine Act, introduced to prevent the incursion of any foreign pest and disease but it has at the same time prevented the development of high-performing varieties as it’s the private sector’s involvement that brought the growth and innovation in rice and maize sector.

At present, hundreds of private companies can be found selling both approved and unapproved varieties across the country with no oversight whatsoever. Officials from Punjab Agriculture Department talking to ProPakistani admitted that they are unable to even make sense of all the varieties available in the market let alone curb the illegal ones.

“SS-32 is an excellent variety that performs well even under the extreme pressure of whitefly pest but it’s unfortunately unapproved and still has been cultivated on more than half of the cotton area which indicates that the system is not working and varieties are slipping into the market before formal approval”, added Motiwalla.

He said that these products are not bad themselves but the way they have been marketed is questionable and this unregulated commercialization is the primary reason for the downfall of our cotton.

Federal Seed Certification and Registration Department (FSC&RD), the regulator responsible for the seed market discipline is understaffed while Pakistan Central Cotton Committee, the federal body that oversaw all R&D with respect to cotton is under a severe financial crisis for years as the majority of textile millers refused to pay cess under the Cotton Cess Act of 1923. It has not just resulted in the curtailment of PCCC operations to a minimum but also threatens a brain drain of scientists.

As the market stands flooded with cheaper alternatives with no quality control, no good company would be willing to enter the market for seed development and marketing. The fraud is so normalized that certain companies buy all kinds of mature and immature seeds from the market and color it with a pink pigment to hide the differences.

Triple Gene varieties introduced recently brought some hope for the industry and for some reason are another cause behind the recent uptick seen in the production. These varieties offer resistance against two kinds of bollworms and glyphosate (herbicide) which enable farmers to control weeds effectively but it’s facing the same market glut of unapproved cultivars, hampering the development of industry that can overcome the evolving challenges.

On one end, there is this mess in the cotton seed industry with no quality assurance mechanism and on the other end, government’s Textile Policy 2020-2025 aims to take exports to $25 billion by 2030 and $50 billion by 2050 with no vision in place to achieve these goals.

Motiwalla suggested that in the short and medium term, the government must introduce gene fingerprinting technology for better variety identification and a ‘survival of the fittest’ approach of banning varieties that have lower performance across the country. He also called for incentivizing farmers for higher-quality cotton at ginning level (the detailed quality check is only done at spinning at present) as that’s the only way, farmers can get more money for the crop.

But most importantly, he emphasized the need for public-private partnerships to source germplasm from around the world and develop cotton varieties as happened with the case of rice where multiple domestic names have partnered with international brands to introduce hybrid cultivars.

“If the government allowed import of germplasm under the proper protocols through legal channels, no unapproved variety will slip into the market and the illegal varieties should be banned from cultivation at all costs” added Motiwalla.

There is also a need for complete crop plans from the government for trial and approval of varieties without which no variety should be allowed to be marketed while companies with sizable expertise and workforce to guide farmers on the best practices should be allowed to operate. If the government is realistically looking to reform the cotton industry and sustainable agriculture production, it is quite impossible without fixing its seed industry by all means possible.

Insightful!

Well researched and informative report. Badly needed some pragmatic initiatives from both Public and private sector.

It is a disgrace. Please put the emphasis on organic cotton. Remove GMO cotton from the market. Thank you